I study the fascinating interplay between a planet’s spin axis and its orbital evolution.

The rate at which a planet spins at, and the direction its rotational axis points, is profoundly important for many reasons. Here on Earth, our axial tilt is responsible for the seasons by regulating the angle of incident flux we receive from the sun. Planetary tilts have strong implications for habitability through atmospheric regulation.

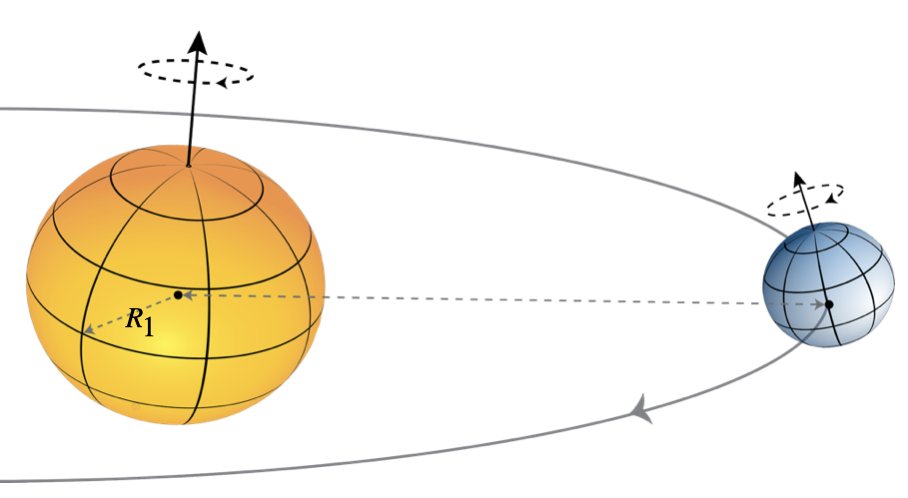

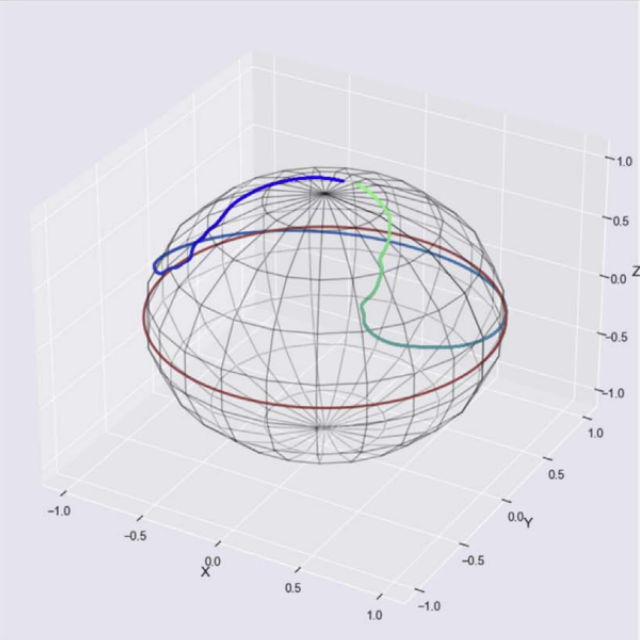

Standard planetary formation theory tells us that planets should form with zero tilt. Yet, if we look at the planets in our solar system, every single one of them is tilted over to some degree. So, what gives? It turns out that gravitational perturbations from the other planets in the system can, in the right conditions, gently tip a planet over time. This process is called spin-orbit resonance, and we think it is responsible for many of the off-axis planets in our solar system. I study the process and implications of spin-orbit resonance, in both our own solar system and in exoplanet systems.

Tilting Uranus

Uranus is the most striking example of a tilted planet in our solar system. With an axial tilt of 98 degrees, one can think of Uranus as rolling through space on its side. While spin-orbit resonance well-explains the tilts of other planets in our solar system, Uranus is trickier: if you look at the planets in our solar system and work out the math, the conditions just don't work out for Uranus in particular. Hence, the most accepted genesis of Uranus' massive tilt is a giant impact. This works! But this theory also comes with its own set of problems.

Our idea: what if there was another planet in the solar system that could change the equation? Enter Planet Nine, a hypothesized giant planet in the outer solar system that's been the subject of an cosmic planet hunt over the past decade. Planet Nine has not been definitively discovered, but if it was out there it would certainly be massive enough to change our calculus. In this work we assessed if spin-orbit resonance could explain Uranus' tilt, in the presence of Planet Nine. The punchline: it can! But it's not terribly realistic -- you need to make a few out-there assumptions about Uranus' structure to make it work.

Relevant Papers:

Planetary Rings Masquerading as a Puffy Planet

We've discovered some pretty strange worlds. Some of my favorite planets are the so-called super-puffs, which have the density of styrofoam or cotton candy. We know of quite a few such worlds, and we think we have a good idea how they formed: a planet very close to its host star gets blasted by a ton of incident radiation and tidal heating, which heats up the planet's interior and puffs it up like a hot air balloon.

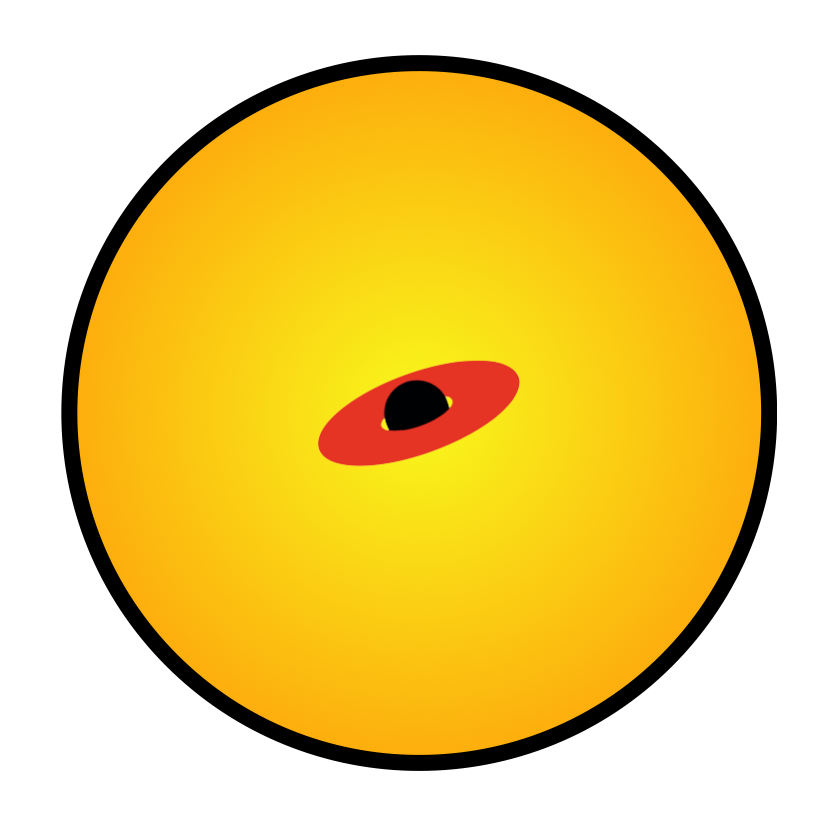

Enter HIP-41378f, a super-puff that is the outermost planet of a five-planet system. HIP-41378f traces an orbit about it's star at a distance between Earth's and Mars'. There's not enough heat this far out for any of the standard super-puff formation mechanisms to work here -- trust me, we'd know if there was. In this work we show that based on the architecture and dynamical history of the system, it would be very surprising if HIP-41378f wasn't tilted over.

Why do we care that it's tilted? Let's think about how astronomers measure density. Density is mass over volume, and we measure volume based on the transit method. Exoplanets, if we're lucky, will regularly eclipse their host stars. We can thus measure volume based on how much light a planet blocks when it eclipses its host star. A very puffy planet would block a lot of light from its host star. But so could a normal planet that has an extensive ring system around it! And you'd need the planet to be tilted over for this hypothesis to make sense -- otherwise, you'd see the thin rings edge-on and they wouldn't block any light. Hopefully, in the near future we'll be able to directly detect planetary ring systems with packages such as squishyplanet, developed by Ben Cassese (a co-author on this study).

This article was covered in PopSci! Check out this wonderful article written by Briley Lewis: What if 'cotton candy' planets are actually Ring Pops?

Relevant Papers: